Examples

Heavy Fermion Behavior in the superconductor YFe2Ge2

The Hund’s metal YFe2Ge2 has garnered recent interest because it is potentially a spin triplet superconductor. This speculation is based on observed strong ferromagnetic response in the spin susceptibility. The most stable superconducting phase of systems with strong q=0 response have spin triplet character, which can form the basis for Majorana Fermions.

The present work, under review in Scientific Reports, involved a collaboration between NLR and CU Boulder. It focuses mostly on one-particle spectra in YFe2Ge2. Since two particle properties (especially spin susceptibility) that drive superconductivity depend very sensitively on one-particle properties, establishing a benchmark for the latter is very important before embarking on a description of superconductivity.

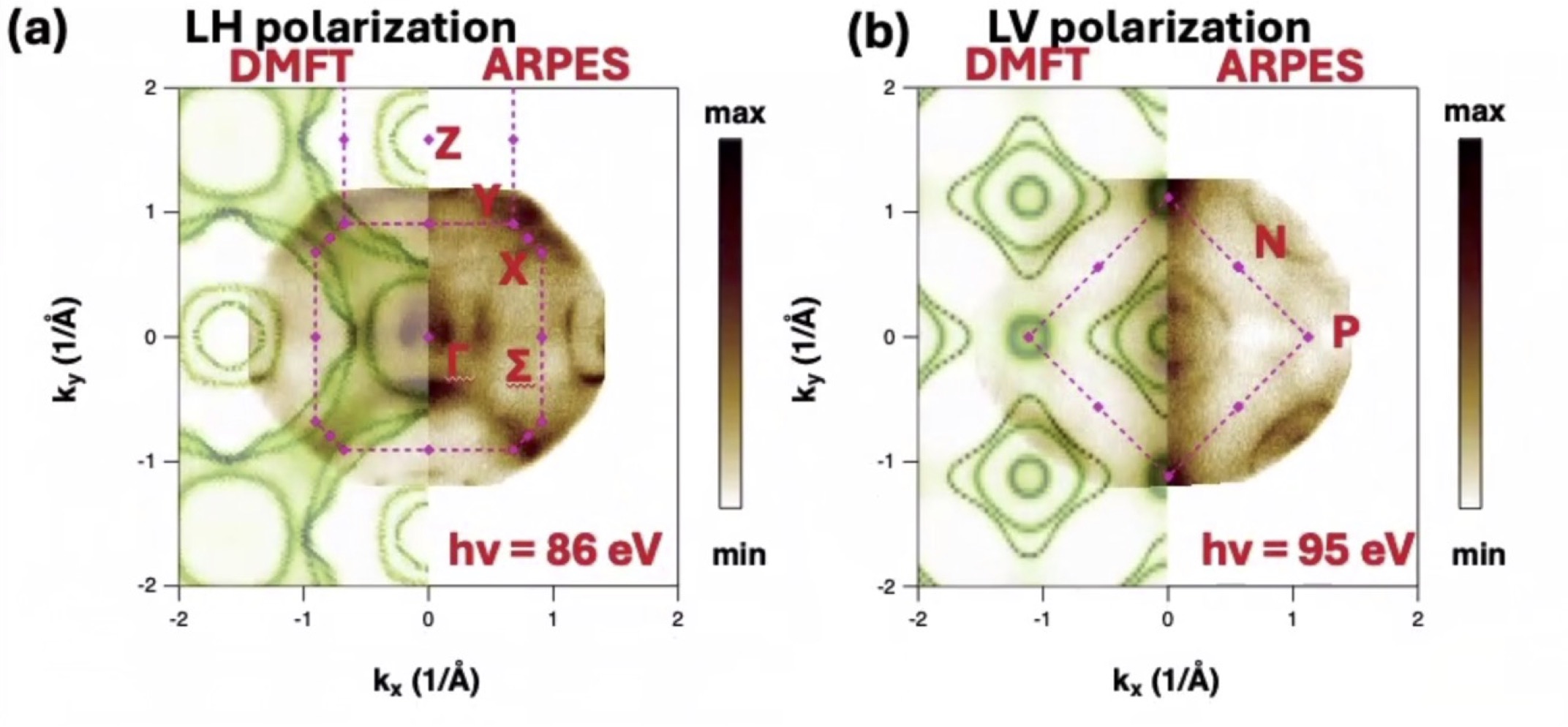

This work combined ARPES measurements with theory, taken from a self-consistent form of many-body perturbation theory (the Quasiparticle self-consistent GW approximation, QSGW) augmented with dynamical mean field theory (DMFT). A DMFT study of YFe2Ge2 had been carried out previously, but the DMFT was used to augment density-functional theory (DFT). Its fidelity is considerably less QSGW+DMFT because QSGW describes the system reasonably well, where as DFT fares much worse. The nonlocal potential in QSGW narrows the Fe d states relative to DFT, and also well aligns states of heterogeneous character, e.g. the Ge and Se p states and the Fe d state, in contrast to DFT. DMFT is still needed because of the lack of spin flip diagrams in the theory. Typically DMFT further narrows the Fe d bandwidth in Hund’s metals relative to QSGW, and that trend is seen in YFe2Ge2 as well. As Fig. 1 shows, the Fermi surfaces predicted by theory and measured by ARPES are in almost perfect agreement. Furthermore, the theory can resolve states by symmetry and orbital character. To some degree ARPES can do this too, by measuring with LH (linear horizontal) and LV (linear vertical) polarized light. Fig. 1 shows what part of the spectral features should be resolved LH light and by LV light, and in both cases agreement is excellent.

Fig. 1. Experimental Fermi surfaces in brown overlaid on the left-half with partially transparent theoretical Fermi surfaces in green calculated using QSGW+DMFT. (a) Z–X–Γ plane measured with hv = 86 eV and LH (linear horizontal) polarization and (b) through the P-N plane measured with LV (linear vertical) polarization and hv = 95 eV. Two pockets around the origin are observed in ARPES. DMFT shows a third, outer pocket, but the symmetry precludes it being picked up by LV polarization.

Fig. 1. Experimental Fermi surfaces in brown overlaid on the left-half with partially transparent theoretical Fermi surfaces in green calculated using QSGW+DMFT. (a) Z–X–Γ plane measured with hv = 86 eV and LH (linear horizontal) polarization and (b) through the P-N plane measured with LV (linear vertical) polarization and hv = 95 eV. Two pockets around the origin are observed in ARPES. DMFT shows a third, outer pocket, but the symmetry precludes it being picked up by LV polarization.

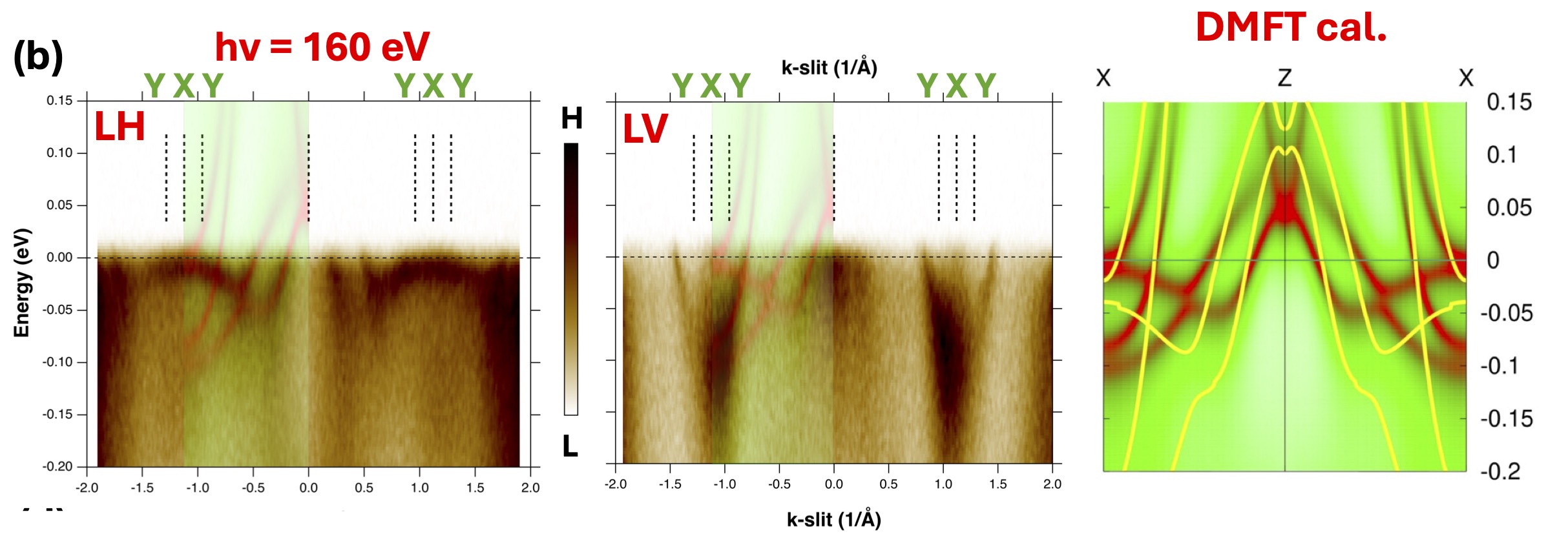

This study uncovered some very interesting new results. First, both theory and ARPES uncovered an extremely flat band only a few meV below the Fermi level at the X point (Fig. 2). The effective mass (both theory and ARPES) was observed to be about 25 times the bare electron mass along the X-Γ line. This is of considerable interest in its own right: Heavy fermion behavior for states very close the Fermi surface provide a rich playground for novel many-body effects. Other Fe based superconductors, e.g. FeSe, also have flat bands; but we learn from theory that the “flatness” comes about for somewhat different reasons. In FeSe (and even more so in FeTe), spin fluctuations are very strong, which imprint pronounced effects on the electronic structure, especially on the Fe dx2-y2 state. The effect is two-fold: the bandwidth gets renormalized, and the state becomes very incoherent. Spin fluctuations have similar effects on YFe2Ge2, but they are weaker. This can be seen for example, in the coherence of the state: d states are much more coherent than in FeSe. Nevertheless, the bandwidth is even narrow than in FeSe.

Why is this? It is because of matrix element effects. These terms (whose origin is one-body in contrast to the spin fluctuations); are very prominent in twisted graphene, for example. Twisted graphene has very flat bands at special magic angles because of mutually canceling hopping matrix elements. To some extent that happens in YFe2Ge2, too. The matrix-element and spin-fluctuation effects combine to make a very flat band.

Fig. 2. ARPES spectra on the X–Y–Z–Y–X line in LH polarization and LV polarizations. DMFT calculations are superimposed using semitransparent green-red color map in the showcasing the excellent agreement between theory and experiment. Right shows the DMFT calculations (red-green color map) in comparison to the QSGW calculations (yellow) upon which the DMFT calculations are based. Bands cross the Fermi level are at similar implying that QSGW and DMFT Fermi surfaces are similar. The QSGW Fermi velocities are roughly twice as large as those in DMFT (and by extension, the experimental) velocities.

Fig. 2. ARPES spectra on the X–Y–Z–Y–X line in LH polarization and LV polarizations. DMFT calculations are superimposed using semitransparent green-red color map in the showcasing the excellent agreement between theory and experiment. Right shows the DMFT calculations (red-green color map) in comparison to the QSGW calculations (yellow) upon which the DMFT calculations are based. Bands cross the Fermi level are at similar implying that QSGW and DMFT Fermi surfaces are similar. The QSGW Fermi velocities are roughly twice as large as those in DMFT (and by extension, the experimental) velocities.

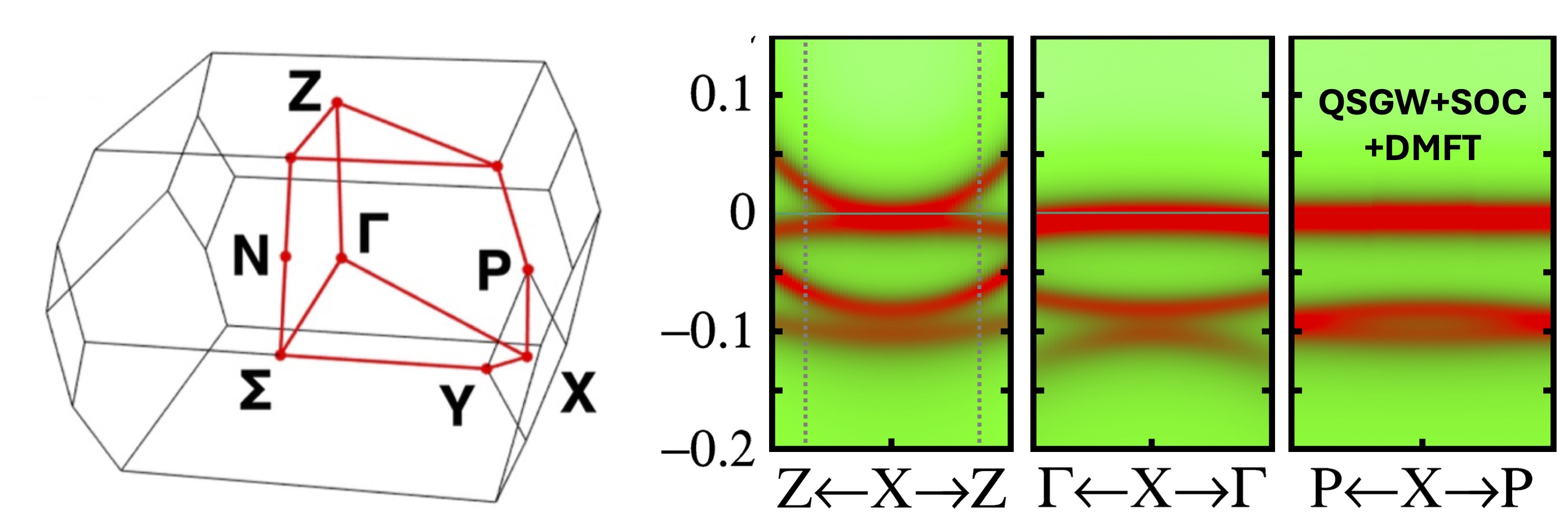

With the theory we can readily explore spectral functions in other directions (Fig. 3). It turns out that dispersions in other directions are quite different: along the X-Z line, the curvature of one of the two bands changes sign; along the X-P line, the bands become almost entirely flat.

Fig. 3. Dispersion of bands around the X point along three orthogonal directions: X–Z, X–Γ, and X–P. All plots are shown in the vicinity of X, with excursions roughly equal to ±0.1⋅2π/a. The electron and hole bands appear just below the Fermi level in all cases. The bands are flat in all directions, but particularly so along P–X–P. Left diagram shows the Brillouin zone with high-symmetry points marked.

Fig. 3. Dispersion of bands around the X point along three orthogonal directions: X–Z, X–Γ, and X–P. All plots are shown in the vicinity of X, with excursions roughly equal to ±0.1⋅2π/a. The electron and hole bands appear just below the Fermi level in all cases. The bands are flat in all directions, but particularly so along P–X–P. Left diagram shows the Brillouin zone with high-symmetry points marked.

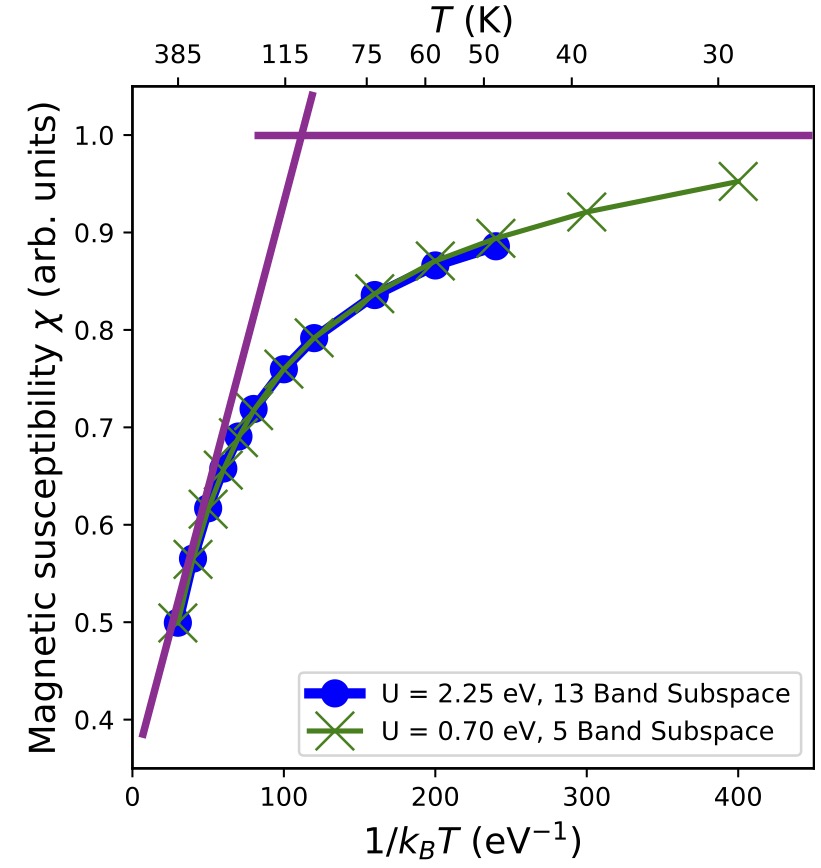

ARPES measurements show a sharpening in the width of the flat band as temperature decreases. This is also seen in DMFT, and it suggests the onset of a Kondo transition. Very strong evidence that there is a Kondo transition can be seen from the temperature dependence of static spin susceptibility as calculated from DMFT. This has important implications for spin triplet superconductivity. Absent Kondo physics, YFe2Ge2 would very likely be a spin triplet superconductor. But, with Kondo physics present at low temperature, the driving force for spin triplet superconductivity is much weakened, and our work suggests that it is likely to be a spin singlet instead. In a future work we will examine this question.

Fig. 4. Calculated on-site static spin susceptibility (the expectation value at one site) as a function of temperature as calculated by DMFT. DMFT was calculated for physically realistic values of Hubbard parameters U and J, and for some small values as well to reach lower temperatures. The behavior is only weakly dependent on the choice of U and J. It shows a transition from Curie-Weiss behavior () to Pauli behavior () at low temperature with the crossover (Kondo) temperature of ∼100 K. The and limits are illustrated with purple lines drawn as a guide.

Fig. 4. Calculated on-site static spin susceptibility (the expectation value at one site) as a function of temperature as calculated by DMFT. DMFT was calculated for physically realistic values of Hubbard parameters U and J, and for some small values as well to reach lower temperatures. The behavior is only weakly dependent on the choice of U and J. It shows a transition from Curie-Weiss behavior () to Pauli behavior () at low temperature with the crossover (Kondo) temperature of ∼100 K. The and limits are illustrated with purple lines drawn as a guide.

PAPERS · FERMI SURFACE · SUPERCONDUCTORS · DMFT